In the world of computer systems, daemons (pronounced "dae-mons") are essential but often invisible entities. These unassuming background processes are responsible for handling critical system-level tasks, providing crucial services, and quietly supporting the smooth operation of your computer. In this technical guide, we will explore what daemons are, how they work, and their significance in various operating systems.

What is a Daemon?

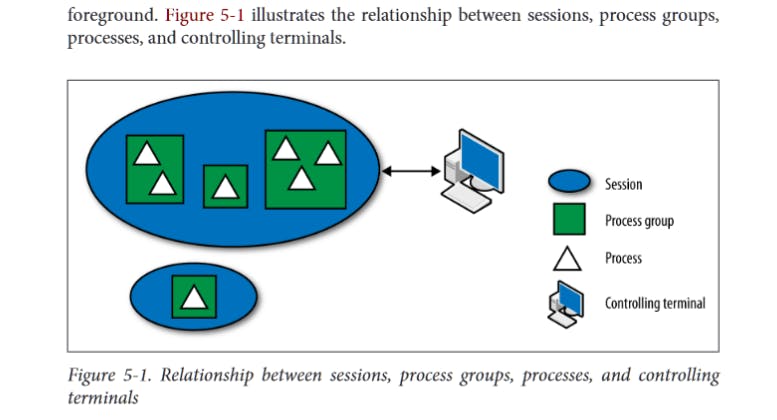

A daemon is a type of process that operates in the background, detached from any controlling terminal or user session. Unlike foreground processes that interact directly with users through a terminal, daemons run independently, diligently executing their designated tasks. Commonly initiated at system startup, daemons serve a wide range of purposes, from network services to hardware management and more.

The Origin of the Term "Daemon"

Characteristics of Daemons

Daemons possess distinct characteristics that set them apart from ordinary processes:

Longevity: Daemons are intended to be long-lived. They often start during system boot and continue running until the system shuts down.

Background Execution: Unlike foreground processes that require a terminal, daemons operate in the background, free from direct user interaction.

Daemons in Linux

In Linux, daemons play a crucial role in system maintenance and operation. They are organized in specific directories based on their importance:

/usr/sbin/: This directory houses system-related executables, including daemons essential for system operation. Examples include sshd (SSH daemon) and httpd (web server daemon)./sbin/: Similar to /usr/sbin/, /sbin/ contains system executables. However, the ones in/sbin/are critical for system maintenance and recovery, such as init and systemd./usr/bin/: Although less common, some daemons may reside in/usr/bin/if they are associated with specific applications and not required for system boot.

the specific locations of daemon executables can vary depending on the Linux distribution and system configuration.

Daemon vs Background Processes - Comparison

To better understand daemons, let's compare them to background processes:

| Daemons | Background Processes | |

| Control | No controlling terminal or user session | Connected to a terminal or user session |

| Execution | Long-lived, running until system shutdown | Short-lived, dependent on user interaction |

| Purpose | System-level tasks and services | User-specific tasks and interactions |

| Examples | sshd, httpd, cron, dhcpd | Text editors, web browsers, shell scripts, etc. |

"all daemons are background processes but not all background processes are daemons"

Summoning Daemons

Daemons are launched during system boot or triggered based on specific events. The initiation process varies based on the operating system and the init system used:

Boot Process: During system boot, the init system (e.g., SysV init, Upstart, or systemd) takes control and starts various system services, including daemons. Init scripts are commonly used in SysV init systems, while systemd relies on unit files.

Triggered Activation: Some daemons are launched on-demand when certain events occur, like network activity or hardware detection.

User Initiated: Users can start daemons manually by running corresponding commands, like httpd or sshd.

Service Managers: Apart from the init system, service managers like systemctl or supervisord can manage daemons.

Creating Your Daemon - An Analogy

Creating a daemon process can be visualized using an analogy with the Space Shuttle Enterprise:

In Image

Creating a Daemon - Space Shuttle Enterprise's Mission

The Space Shuttle Enterprise: In our analogy, the Space Shuttle Enterprise represents the script we want to turn into a daemon. It's a well-prepared and self-sustaining spacecraft, ready for its mission. Similarly, we create the daemon script with all the necessary features and functionalities.

Launching from the Carrier Aircraft: To become a daemon, the script must first be detached from the current terminal session. This step is similar to the Space Shuttle Enterprise launching from the carrier aircraft, where it separates itself from the platform that initially held it (the carrier aircraft).

Executing Safely: As the Space Shuttle Enterprise detaches from the carrier aircraft, it continues its mission independently, ensuring a safe distance to avoid any potential collisions. Similarly, the daemon script executes as a background process, safely distanced from the terminal and user interaction.

The Orbiter and the Carrier Aircraft: The Space Shuttle Enterprise consists of two major components: the orbiter (spacecraft) and the carrier aircraft (the Boeing 747). The orbiter represents the daemon script, and the carrier aircraft represents the current terminal session.

The Forking Maneuver: Just as the Space Shuttle Enterprise undergoes a forking maneuver to separate the orbiter from the carrier aircraft, the daemon script executes a forking operation in the background. In the analogy, the "forking maneuver" ensures that the daemon script is no longer tied to the current terminal session but operates independently.

The Orbiter in Space: After the safe separation, the orbiter continues its journey in space. Similarly, the daemon script continues to run independently in the background, free from direct terminal control.

Ground Control: Although the Space Shuttle Enterprise is autonomous in space, it remains in communication with ground control. In the same way, the daemon script may communicate with other processes or the system, and its behavior can be managed using a daemon manager or system tools.

Landing Preparation: When it's time for the Space Shuttle Enterprise to return to Earth, it enters the landing phase. Similarly, a daemon can be stopped or paused gracefully when no longer needed or when the system is shutting down.

Safe Landing: The Space Shuttle Enterprise lands safely after completing its mission, representing the successful execution and safe exit of the daemon script.

By using the analogy of the Space Shuttle Enterprise's safe landing, we can understand the process of creating a daemon in a more relatable context. Just like the Space Shuttle Enterprise operates independently from the carrier aircraft, a daemon runs in the background, detached from the current terminal session, and performs its task autonomously.

Having understood what is required of us, we can now do it in code.

DIY-Daemon Guide: Creating a Daemon and Its Manager in Bash

Step 1: Create the Daemon Script

First, let's create the daemon script. Save the following code in a file named my_daemon.sh:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Indefinitely writes "Daemon Running!" message to the file /tmp/my_process

# In between every message, the program pauses for 2 seconds

while true; do

echo "Daemon Running!" >> /tmp/my_process

sleep 2

done

Step 2: Convert the Script into a Daemon

Now, we'll convert the script into a daemon using the common Unix-like system method. A daemon needs to be detached from the invoking session and run in the background.

Here's the updated my_daemon.sh script:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Indefinitely writes to the file /tmp/my_process

# In between every "Daemon Running!" message,

# the program should pause for 2 seconds

# Function to handle the termination signal (SIGTERM)

function handle_shutdown {

echo "SIGTERM : Stopping daemon..."

# cleanup created files if the daemon was running

rm -f /tmp/my_process /var/run/my_daemonPID

# Exit gracefully

exit 0

}

# Set the trap to handle SIGTERM in case of system shutdown while running

trap handle_shutdown SIGTERM

# Remove unnecessary variables from the environment (optional)

unset DISPLAY

# Execute as a background task by forking and exiting

(

# Fork and exit again to prevent acquiring a new controlling terminal(tty)

(

# Set the root directory (/) as the current working directory

# to avoid locking any file system

cd /

# Change the umask to 0

umask 0

# Redirect standard i/o and error streams to /dev/null

exec 0</dev/null 1>>/tmp/my_process 2>>/tmp/my_process

# Close all other file descriptors inherited from the parent process

exec 3<&- 4<&- 5<&- 6<&- 7<&- 8<&- 9<&- 10<&- 11<&- 12<&- 13<&- 14<&- 15<&-

# The actual daemon code we wrote

while true; do

echo "Daemon Running!"

sleep 2

done

) &

# store the PID of the daemon in a file for reference

echo $! > /var/run/my_daemonPID

) &

Notable

Step 3: Create the Daemon Manager

Now that we have our daemon, let's create a simple daemon manager script named my_daemon_manager.sh. This script will handle starting, stopping, and monitoring the daemon:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Define the path to the daemon script

DAEMON_SCRIPT="./my_daemon.sh"

# Function to start the daemon

start_daemon() {

if [ -f "/tmp/my_process" ]; then

echo "Daemon is already running."

else

$DAEMON_SCRIPT

echo "Daemon started."

fi

}

# Function to stop the daemon

stop_daemon() {

if [ -f "/tmp/my_process" ]; then

kill $(pgrep -f "$DAEMON_SCRIPT")

rm /tmp/my_process /var/run/my_daemonPID

echo "Daemon stopped."

else

echo "Daemon is not running."

fi

}

# Function to check the daemon status

status_daemon() {

if [ -f "/tmp/my_process" ]; then

echo "Daemon is running."

else

echo "Daemon is not running."

fi

}

# Main script logic

case "$1" in

"start")

start_daemon

;;

"stop")

stop_daemon

;;

"status")

status_daemon

;;

"restart")

stop_daemon

start_daemon

;;

*)

echo "Usage: $0 {start|stop|status|restart}"

exit 1

;;

esac

Step 4: Usage

Now that we have both the daemon and its manager scripts ready, you can use the manager script to control the daemon:

To start the daemon:

sudo ./my_daemon_manager.sh startTo stop the daemon:

sudo ./my_daemon_manager.sh stopTo check the daemon status:

sudo ./my_daemon_manager.sh statusTo check the daemon running with no controlling TTY:

ps faux | grep my_daemon

Congratulations! You've successfully created a daemon and its manager in Bash. Your daemon will now indefinitely write "Daemon Running!" to the /tmp/my_process file, pausing for 2 seconds between each message. The manager script allows you to start, stop, and check the status of the daemon easily.

References

Robert Love - Linux System Programming Talking Directly to the Kernel and C Library-O'Reilly Media (2013)

Kerrisk, Michael - The Linux programming interface a Linux and UNIX system programming handbook-No Starch Press (2018)

more about Shuttle Carrier Enterprise here